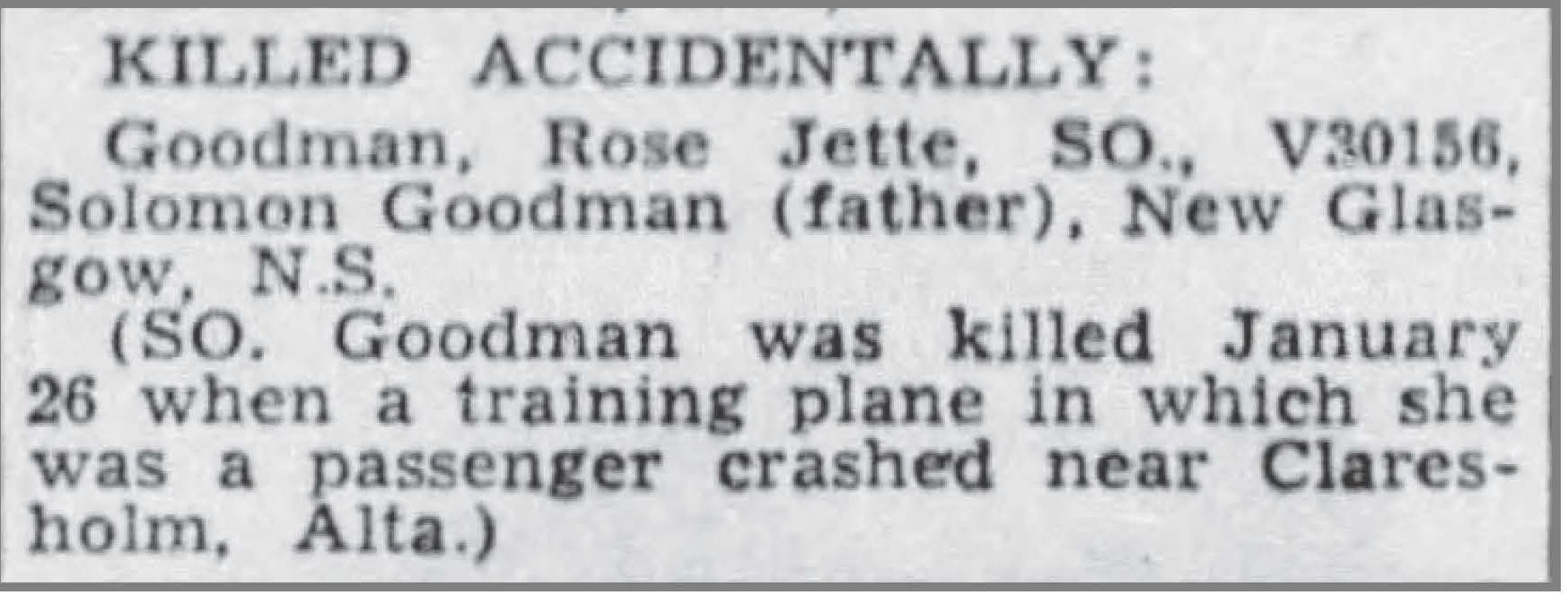

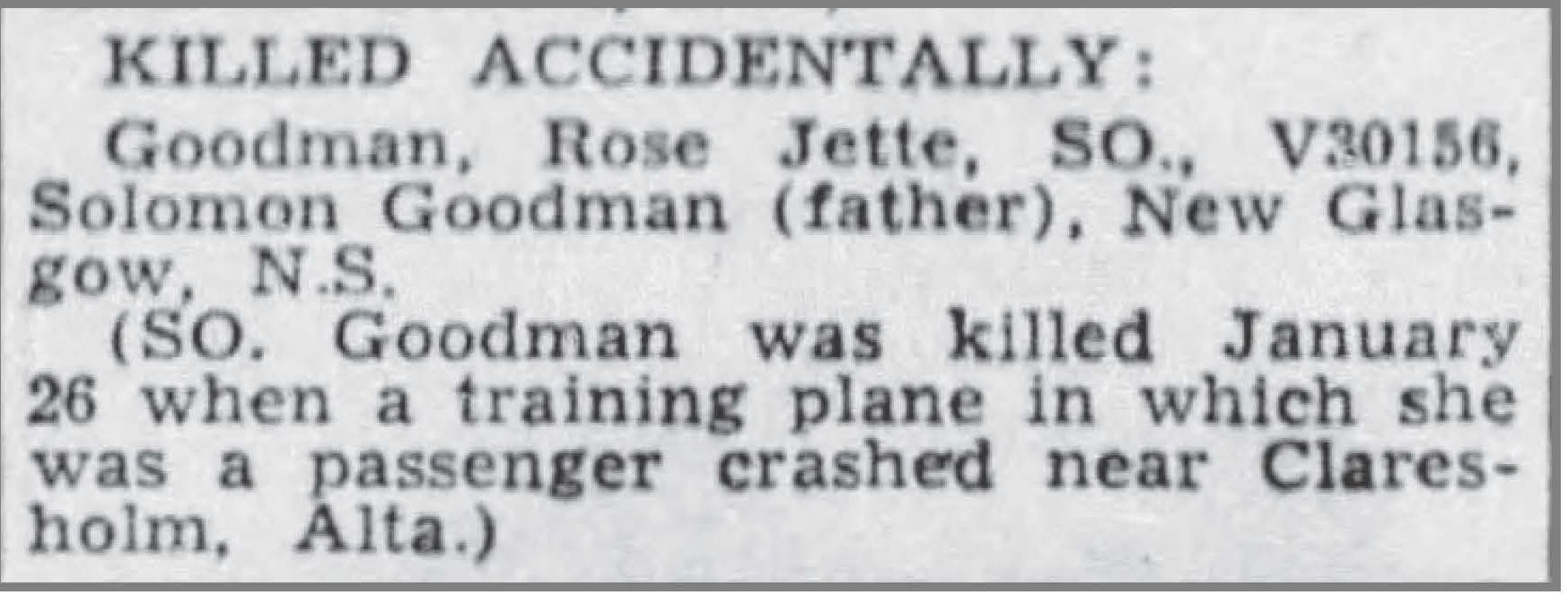

June 19, 1919 - January 26, 1943

Rose Jette Goodman was the daughter of Solomon and Jeanette Goodman. Her parents were Canadian citizens since 1911, immigrating from Austria. (Mr. Goodman was a merchant and partner in a department store with three locations in Nova Scotia.) She had three sisters: Ruth, Anetta and Edith. (Edith passed away in August 1941.) Rose was born in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia on June 19, 1919. The family was Jewish.

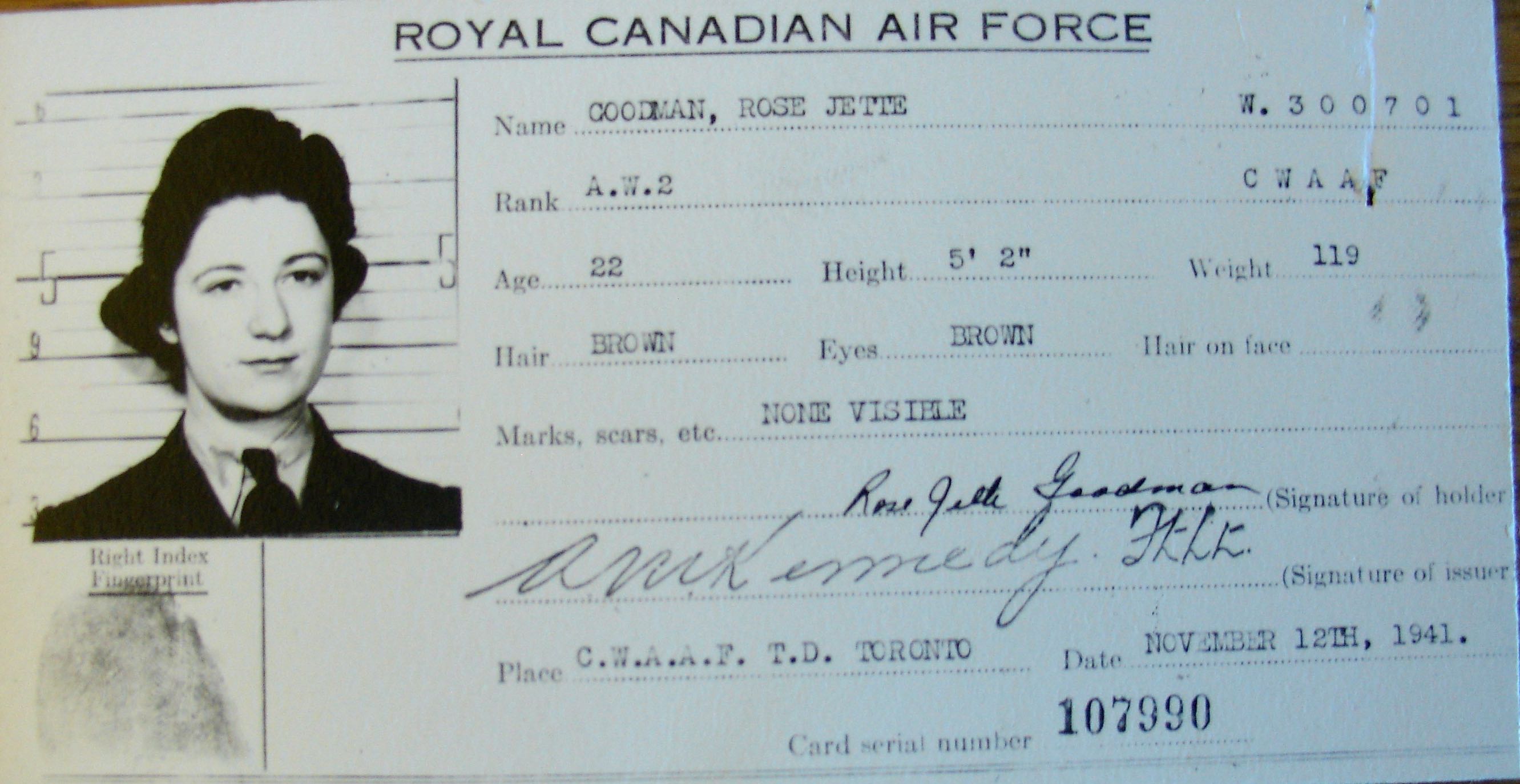

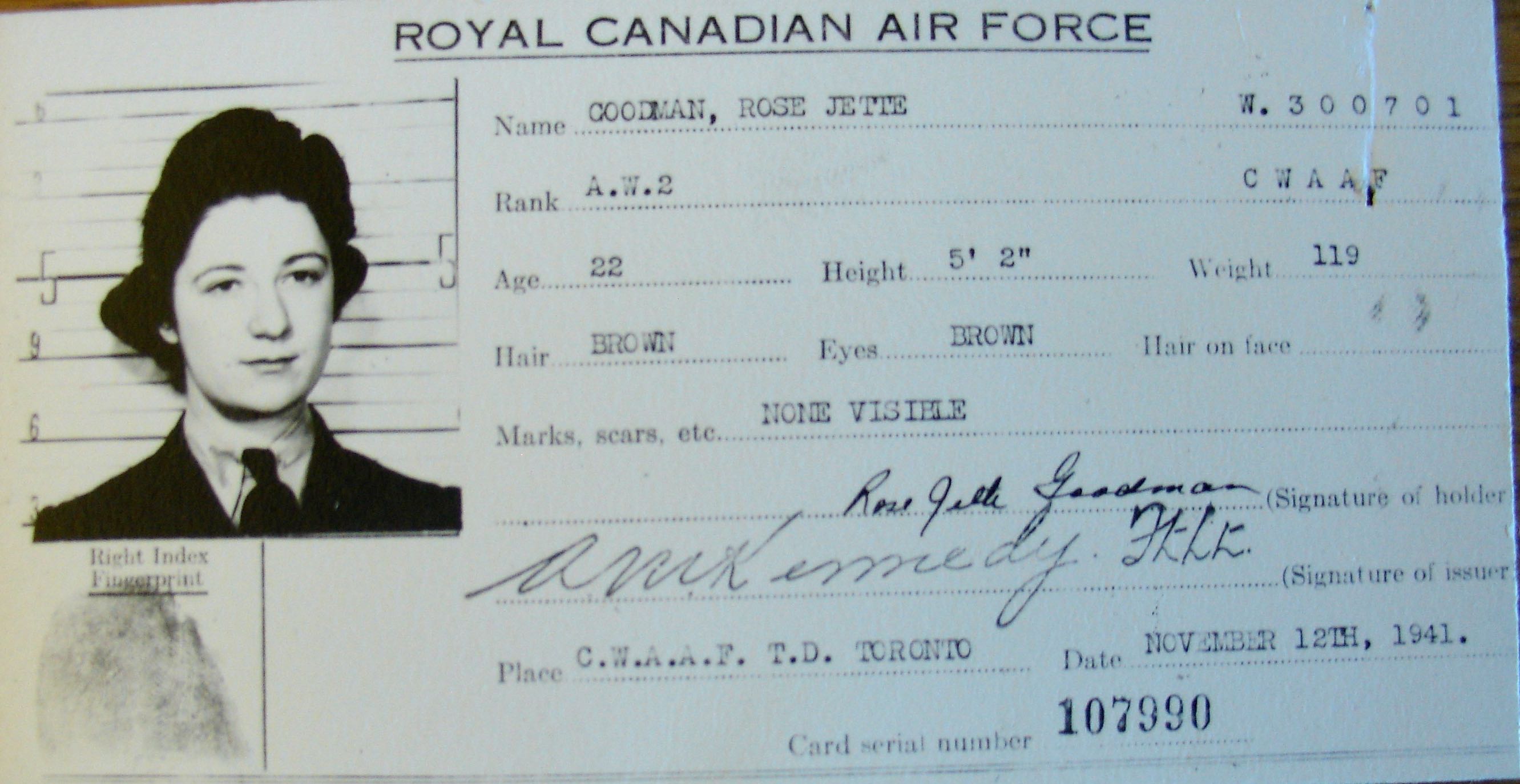

Rose Goodman stood 5'2 1/2" tall, weighed 133 pounds, had a fresh complexion, brown eyes and dark brown hair.

She attended New Glasgow Common School from 1925 - 1933, then attended New Glasgow High School, from 1933-1937, earning her senior matriculation. She was a Girl Guide for eight years. She attended Dalhousie University, from 1937-1941, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree. She was the Class of '41 Life Vice President. She was a member of the University Alumnae Association as well as part of the Deltagama Sorority. She had been an office clerk in her father's business for six months before enlisting.

She enjoyed playing basketball and volleyball, moderately, plus swimming. She listed sports as her hobbies. She also played the violin. On her personal history report dated October 2, 1941: "Net worth: $780." Her father's net worth was also listed: $100,000 (in 2020: $1.5M), "and has an income of about $10,000." The family "has been living in New Glasgow for a long time and are a good class of citizens and are loyal subjects. While at college, she was interested in dramatics...her associates are all of a good class. She has a good reputation and character." She was noted as a "capable girl full of ideas."

In October 1941, she enlisted with the RCAF (WD). Her character and trade proficiency: "Very good and superior." Remarks of her Unit Commander: "Corporal Goodman is a hard worker, reliable, good drill instructor." She was intelligent, good natured, and industrious. She was also noted as an "attractive Hebrew" on one of her forms. She took the St. John's Ambulance course, Home Nursing, October 1941 - November 1941, the Administrative Course, No. 6 "M" Depot January - February 1941 and the Physical Instructor's Course at the same location. In December 1941: "Sound but needs experience and confidence." In February 1942: "A stimulating and interesting instructress." She took the Officer's Training Course #44 and passed in July 24, 1942 with a 73.7% average, 8th out of a class of 34. "Has improved immensely with station experience. Keenly interested in her work and in the services -- efficient and will do well."

In early July 1942, she was in Moncton, NB at No. 8 SFTS, with the rank of A/Sgt in the Special Reserve of the RCAF Administrative Branch (WD).. Then travelled to No. 6 Manning Depot, Toronto for two days. She was posted to No. 15 EFTS Claresholm, Alberta by July 24, 1942.

On December 7th, 1942, at No. 15 EFTS: "This officer is receiving constant instruction on all phases of her work. This officer has brought a lot of enthusiasm and energy to her work. She is rather young, but has done a good job and with experience, will do even better. Recommended for promotion." She was appointed to rank of Acting Section Officer effective December 15, 1942.

In December 1942, S/O Goodman had influenza, noted as "general malaise." She had had her appendix removed in 1934

Section Officer R. J. Goodman was a passenger in the left hand pilot's seat, in Cessna Cran 8739, piloted by P/O Peter Douglas Meyers (J14002), returning to Claresholm on a cross country flight from Lethbridge, Alberta. The crash took place at approximately 2015 hours in a field seven miles east of Woodhouse Siding, 10 km south of Claresholm, Alberta. The aircraft went into a spiral dive then crashed. Goodman was killed instantly with Meyers slightly injured. A Court of Inquiry was struck on January 27, 1943 with eleven witnesses. The weather was noted as "cold front came on and blotted out visibility. The weather at the time was high overcast, scattered clouds, 1000 to 1200 feet, temperature between -4 and -8F. Pilot tried to drive through it and went into a spiral spin. Inability of pilot to maintain or recover equilibrium by instruments." Recommendations: "The necessity of constant instrument flying practice be more strongly stressed."

The RCMP investigated. Mr. Hector Rose, a farmer in the area, testified he had been listening to the radio newscast at 8 pm and shortly afterwards heard the roar of an airplane which seemed above his house. His dog started to bark. He went outside and saw an RCAF Officer coming across the yard who came into the house to ask to use the telephone, as he had crashed. Mr. Rose then drove him to meet the ambulance at Woodhouse, located south of Claresholm, where another telephone call was made at Mr. Sutherland's home. An RCAF car arrived and took them back to the farm. They located the wreckage of the Cessna about 11:30 pm. Mr. Rose said, "The officer whose plane had crashed was cut on the forehead and had an injured leg. He told me there was a lady traveling with him in the plane and he did not know what happened to her." The second witness, S/L Lawson, the Senior Medical Officer at No. 15 SFTS, Claresholm, was off duty at the time, but proceeded to the hospital because of the crash. "S/O Goodman was brought to the hospital and F/L Black told me that she was dead. P/O Meyers was living and was given treatment...there were surprisingly few signs of external injuries, making it impossible to determine death from an external examination." The coroner from No. 4 Training Command, Regina, was sent to perform the autopsy. "From the position of the contusion on the back of her head, it would be inferred that S/O Goodman was facing the back of the plane, and in all probability, was thrown backwards, striking her head against some hard flat substance," S/L Lawson concluded. Meyers was transferred to Macleod and was unable to be interviewed at that time.

Later, his statement was recorded at the Court of Inquiry: "At approximately 6:30 PM p.m. January 26, 1943, accompanied by three passengers, J13474 P/O Charles Rainsforth, C12934 Mrs. Charles Rainsforth, and V30136 S/O Rose Goodman, I left Claresholm in Crane 8739 for Lethbridge. On the way down to Lethbridge, it appeared to me that the artificial horizon was approximately 10° off, and we were forced down to approximately 500 feet above the ground level, due to the spotty weather around Granum. At the time, we passed Pearce, we climbed to 2000 feet, and encountered no more bad weather before reaching Lethbridge. We stayed until P/O Rainsford and Mrs. Rainsford boarded the TCA aircraft and took off for Vancouver. I then telephoned the control tower and asked for clearance to leave for Claresholm. I was cleared and assigned a runway for take off. After taking off, I circled the aerodrome and checked my artificial horizon, which at this time seemed to be functioning properly. At 5500 feet above sea level, I set course for Claresholm, flying 250° magnetic. I later altered course to 240°. After we had passed Monarch, the lights I had been watching were obliterated completely. At first I thought it was just the same patch of cloud I have encountered going to Lethbridge, but later as I could still see no lights, I decided to let down with the intention of descending so far, and if I did not break through, return to Lethbridge. I was approximately 5500 above sea level when I started to let down at approximately 500 ft./minute at 120 mph. I must have been letting down for about 2 to 3 minutes, when I noticed that I was in a bank of about 30° to the right. I started to correct, but for some reason could not get the artificial horizon to go back to neutral. I checked to see if I was applying wrong aileron and was using corrective procedure for recovery from a spiral dive. I checked the turn and bank indicator, which indicated a turn to the right, and try to straighten it out with the rudder. By this time I must’ve been at the height of about 1200 feet above ground level, and I realized it was getting pretty serious and told S/O Goodman to jump. I turned back and was busy trying to get the aircraft out of the spiral dive. A few seconds later I turned around and saw that Goodman had not started to get ready to jump. I yelled at her again. She leaned forward in her seat and then fell back exhaling as she did so. The dive was pretty bad and I came out of the overcast but by that time I just could not tell what position I was in. I saw the lights, and just shortly after that I hit what I presumed to be the ground, and the aircraft scraped through what I thought was snow. The next thing I remembered which must have been about 10 to 15 minutes later, I got up. My ears were frozen. I’m not quite sure what I was doing but I looked for the aircraft and went over to it. It was very dark and there was no moon at the time. I called for Goodman several times and could not see any sign of her, so I decided to go for help as I did not know how badly I was hurt and if I was going to remain conscious. I thought the best idea was to go for help immediately. I started out for what later turned out to be the light of our relief aerodrome at Woodhouse, and on the way I saw shadow of what I thought might be buildings or trees. It turned out to be buildings. At the house I telephoned the airdrome at Claresholm and gave them what information I could about the crash."

"After reaching the farmhouse and telephoned Claresholm, I drove to the highway with the farmer to meet the ambulance. I told the farmer that I had a passenger with me but as I was not sure of the location of the crash, I thought it best to go and meet the ambulance as soon as possible... I did not anticipate any trouble due to the weather conditions were leaving Lethbridge. I had no flashlight in the aircraft with me. This aircraft have not been tested and certified as serviceable for night flying. I said I would night test it myself on the way to Lethbridge. I can say that it was serviceable for night flying, all night flying equipment was working. I have done no instrument training in the last month. I had full permission to carry S/O Goodman in a service aircraft on the night of January 25, 1943."

P/O Meyers was asked many questions during the Inquiry. "When you told S/O Goodman to jump, what did she say?" He responded, "She screamed, 'Oh Pete!' and made a movement to jump." There were questions asked about the amount he had had to drink as there had been a wedding. The witness said, "He did not even have a chance in taking part in the toast....there is no question in my mind from observation and knowledge of this officer that he did not even have a cocktail." He was not allowed to consume alcohol because of a duodenal ulcer. [Elimination of alcohol was necessary, it was noted by the Accident Investigation Branch Group Captain, F. S. Wilkins, on the grounds of medical disability, not because of the pilot's previous abuse of alcohol."] The ninth witness, F/L Thomas Black, MO at No. 2 Wireless School in Calgary, on temporary duty at No. 15 SFTS, Claresholm, stated, "I succeeded in reaching in and removing the flying boot from the left foot [of S/O Goodman] and examined it for any sign of life," as the aircraft was resting on its back and he had seen the legs of a body protruding from the wreckage. "The only part of the body that was in the clear was that below the hips. The remainder was covered by general wreckage. It could not be moved by the three men present. When the rest of the party arrived...the body was removed. It may be noted the body was lying in the snow. The seat pack was intact...Pilot Officer Meyers had a large contusion on the right side of his thigh; there was a possibility of his thigh being fractured. ...he was given morphine...the accident upset him considerably and to deaden any pain which he might be suffering...at the hospital, it was found he was suffering only from mental shock and two very minor scratches on his face."

The tenth witness, S/L Derrek Atkinson, stated that P/O Meyers had been given verbal permission to fly P/O Rainsforth and Mrs. Rainsforth to Lethbridge to catch their TCA flight to Vancouver but was not authorized on a form. P/O Meyers was also noted not to have had instrument time during the month of January.

The twelth witness, G/C Walter Edmund Kennedy, Commanding Officer of No. 15 SFTS, Claresholm, stated, "On January 26, 1943, I gave permission for P/O Rainsforth and Nursing Sister Rainsforth to be flown to Lethbridge by P/O Meyers to catch the TCA plane there. I did not give permission for Section Officer Goodman to proceed on the flight because her name was not raised in the discussion. I would like to make clear this point, however, as there appears to have been room for natural misunderstanding as to whether or not S/O Goodman had my approval for the flight and if a request had been made that she be permitted to proceed on the flight, there would have been no official objection to it."

In the conclusions of the Court of Inquiry, it stated that there had been a wedding at the Unit in which P/O Rainsforth, an instructor, and Nursing Sister H. Broad were married. S/O Rose Goodman was bridesmaid and P/O Meyers was best man. The CO of the Unit verbally authorized the use of an aircraft for the purpose of flying the newlyweds to Lethbridge, 44 km ESE of Claresholm. The party included S/O Goodman. They took off in Crane 8937 at 1830 hours. "The pilot and S/O Goodman waited at Lethbridge until the bride and groom took off on the TCA plane for Vancouver...Meyers telephoned the control tower and asked for clearance...at 1200 feet, the pilot told S/O Goodman to jump, but she hesitated, he told her again to jump but she didn't; either she was too frightened or didn't know how to abandon an aircraft....The aircraft nosed up, striking the ground with both engines and wings, it then bounced approximately 200 feet and finally came to rest in an inverted position facing west.. It is presumed that the passenger at this time received the injury at the back of her head, revealed in the autopsy, and was carried along with the aircraft which travelled further for some distance and overturned on its back...the pilot was thrown clear, lost consciousness for a few minutes, then in a dazed and injured condition, with ears frozen, called on his passenger but there was no response. The body of the passenger was found plunged face down in the snow covered ground with part of the wreckage of the aircraft lying across the trunk of her body. No apparent effort had been made by the passenger to extricate herself, presumably having been rendered unconscious by the head injury. The cause of death was undoubtedly due to suffocation as evidenced by the circumstances in which the body was found plus the autopsy findings of very dark blood and engorgement of lungs and other visceral organs." Other findings: "It is considered that a CO of a Station has no authority to authorize the use of Service aircraft to transport a wedding party; not only has he no authority, he is forbidden to do so." Further comments: "P/O Meyers has a medical category of A2hBh with flying limited to four hours per day and 80 hours per month. He was given this category because on November 25, 1942, he was found to have a duodenal ulcer. He was put on a special diet and with this treatment, his symptoms subsided. At the time of his last examination, January 11, 1943, he had shown improvement, felt well and had no symptoms."

On the medical certificate, S/O Rose Goodman's cause of death was compression of the brain, cerebral trauma, but the coroner also found pulmonary congestion and oedema.

P/O Meyers name in many of the newspaper articles was misspelled and/or his initials incorrect. He was also involved in the case of Nursing Sister Marion Mercedes Westgate. Please see her story for more details. Meyers married in February 1944. After the war, he became a lawyer and volunteered with the Kinsmen Club, rising through its ranks. In 1972, he became secretery for the federal Oil and Gas Commission. He died in 2000 as the result of a car accident in the Victoria, BC area. In the Times Colonist, June 3, 2000, he was praised for his work on the MacKenzie Valley Pipeline. His daughter described her father as a man of integrity and principle who stood by his well-thought-out beliefs.

In the list of personal effects, Rose Goodman had a portable, homemade radio, clothes, toiletries, notebooks, writing cases, stationary, jewellery, including a diamond ring, fraternity signet ring, gold wrist watch and identification bracelets. Mr. Goodman wrote a letter to the Chief of the Air-Staff L. S. Breadner, Feburary 9, 1943: "On behalf of Mrs. Goodman and myself, I wish to thank you for the sympathetic letter of January 28th. The loss is a heavy one and is keenly felt and bears out again that the price of liberty is not money but BLOOD, TEARS and SWEAT."

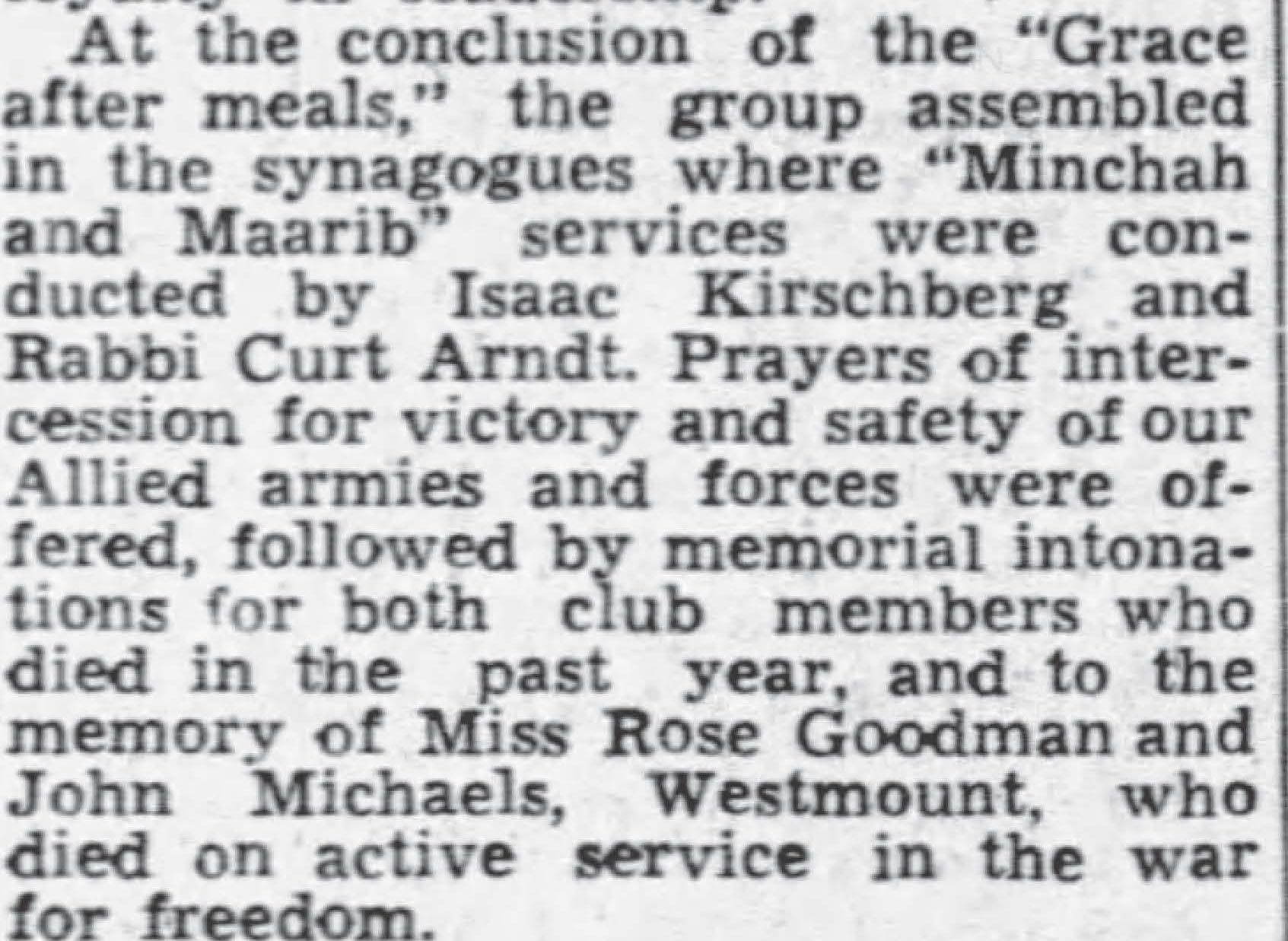

Section Officer Rose Jette Goodman is buried in the Spanish and Portuguese, Jewish Congregation Cemetery, Mount Royal, Outremont, Quebec, the Montreal (SHAAR HASHOMAYIN) Cemetery. Her body was escorted from Calgary to Montreal by F/L Staner, an officer of the Jewish faith from No. 2 Wireless, Calgary.

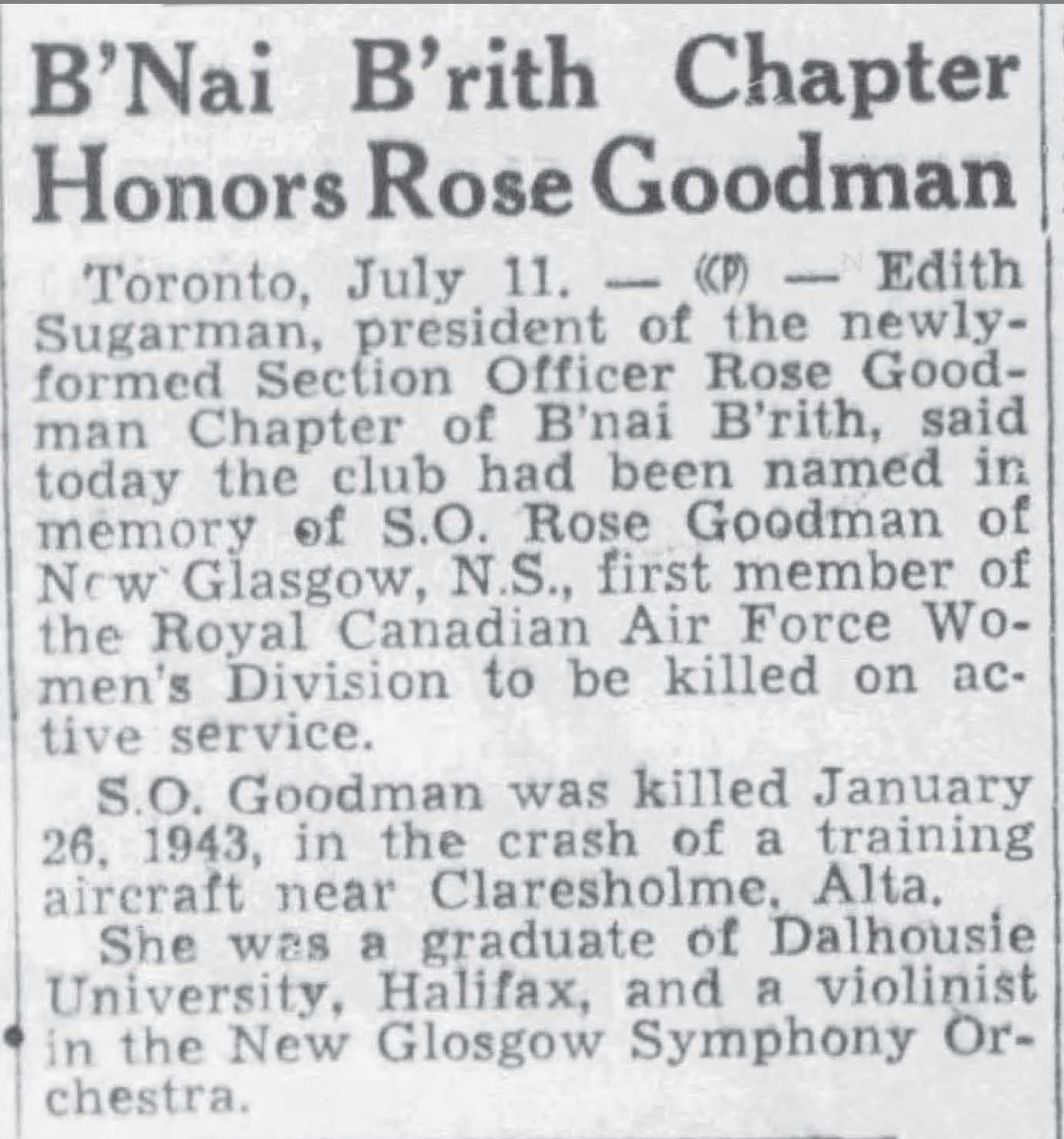

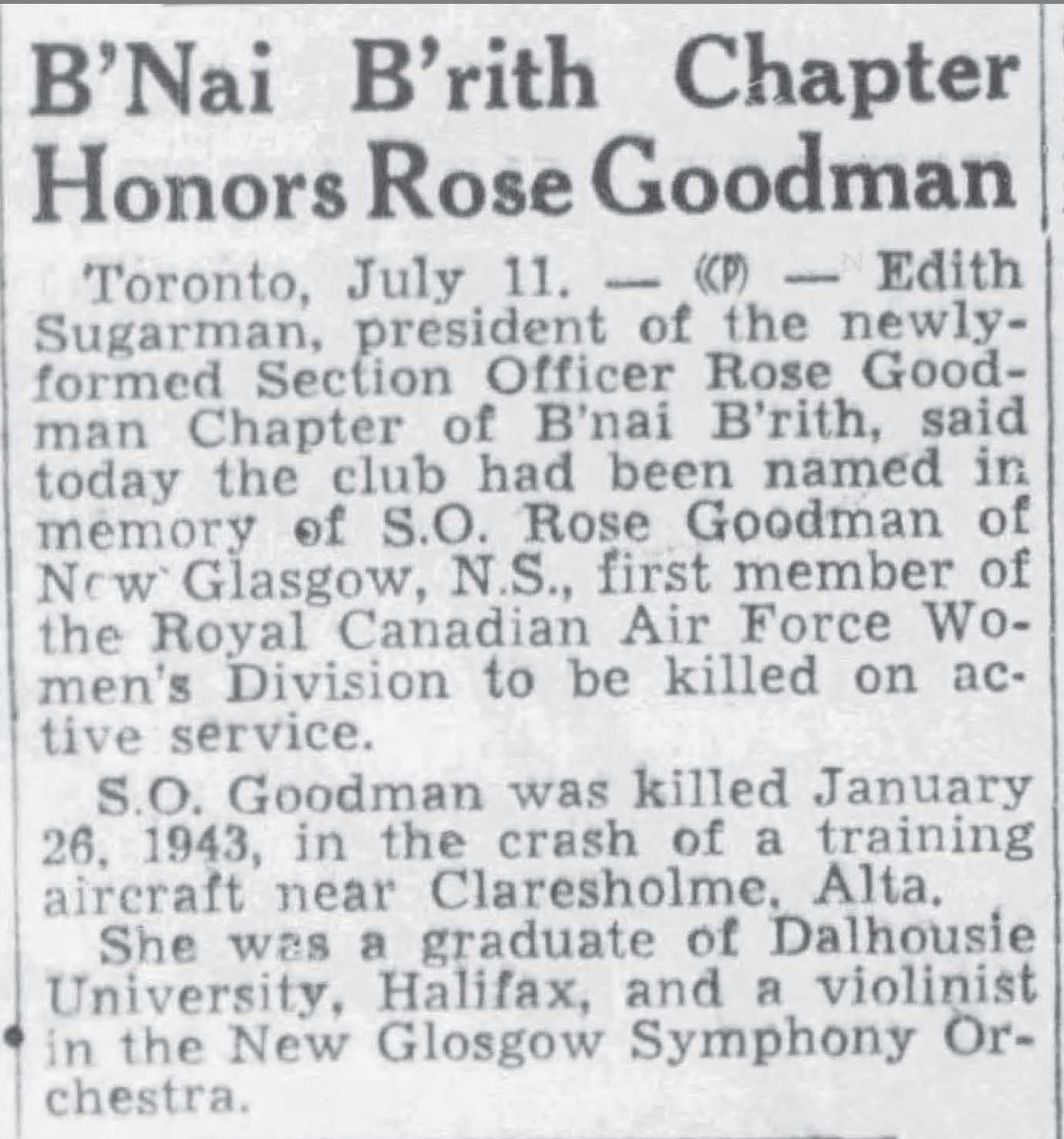

Section Officer Goodman was the first woman casualty of Dalhousie University and the first woman RCAF WD Officer killed in World War Two. In July 1946, a group of young women in Toronto named their club in Goodman's honour. See article above.

LINKS: